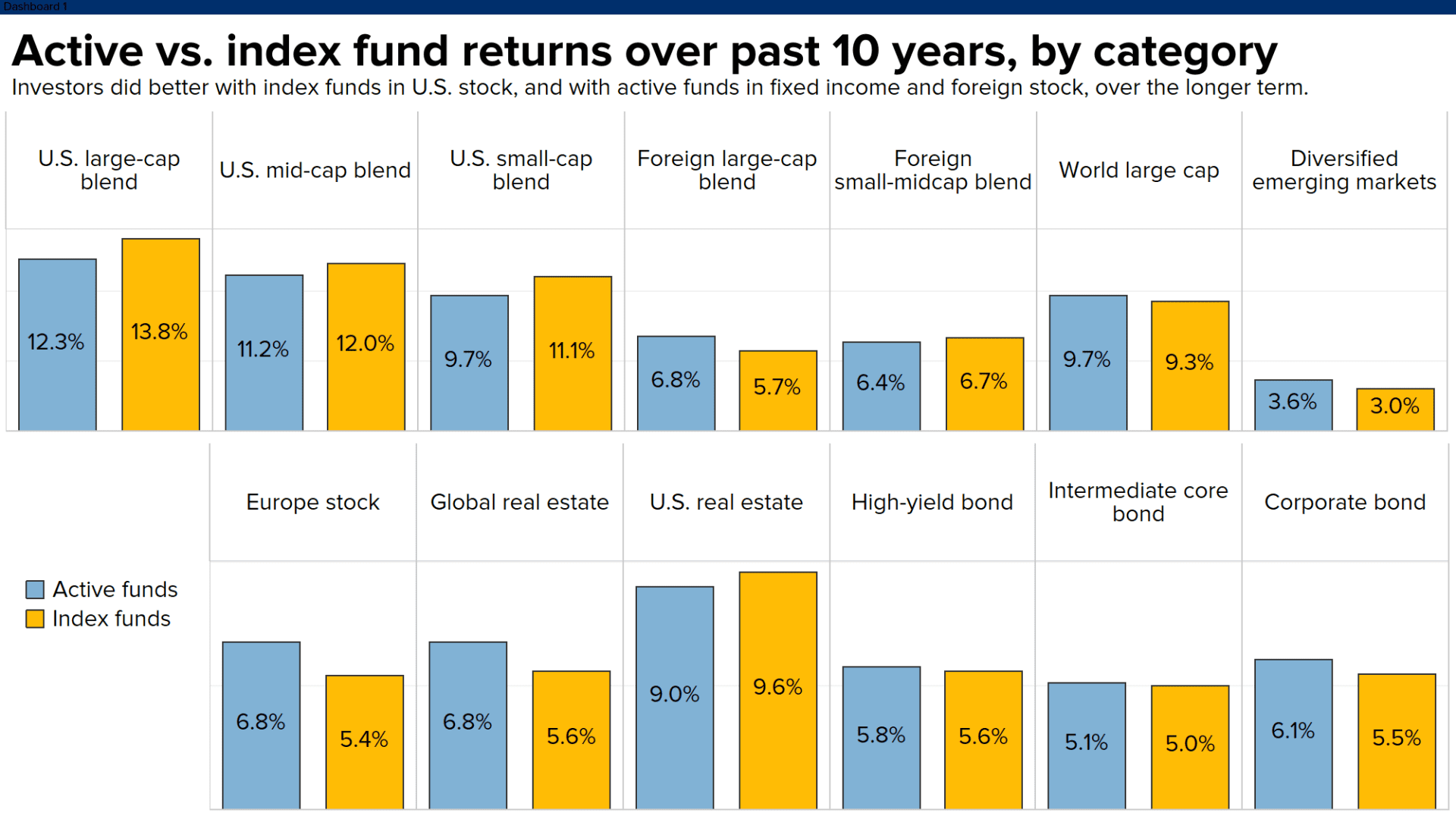

- Investors generally fare better in index mutual funds and exchange-traded funds versus their actively managed counterparts.

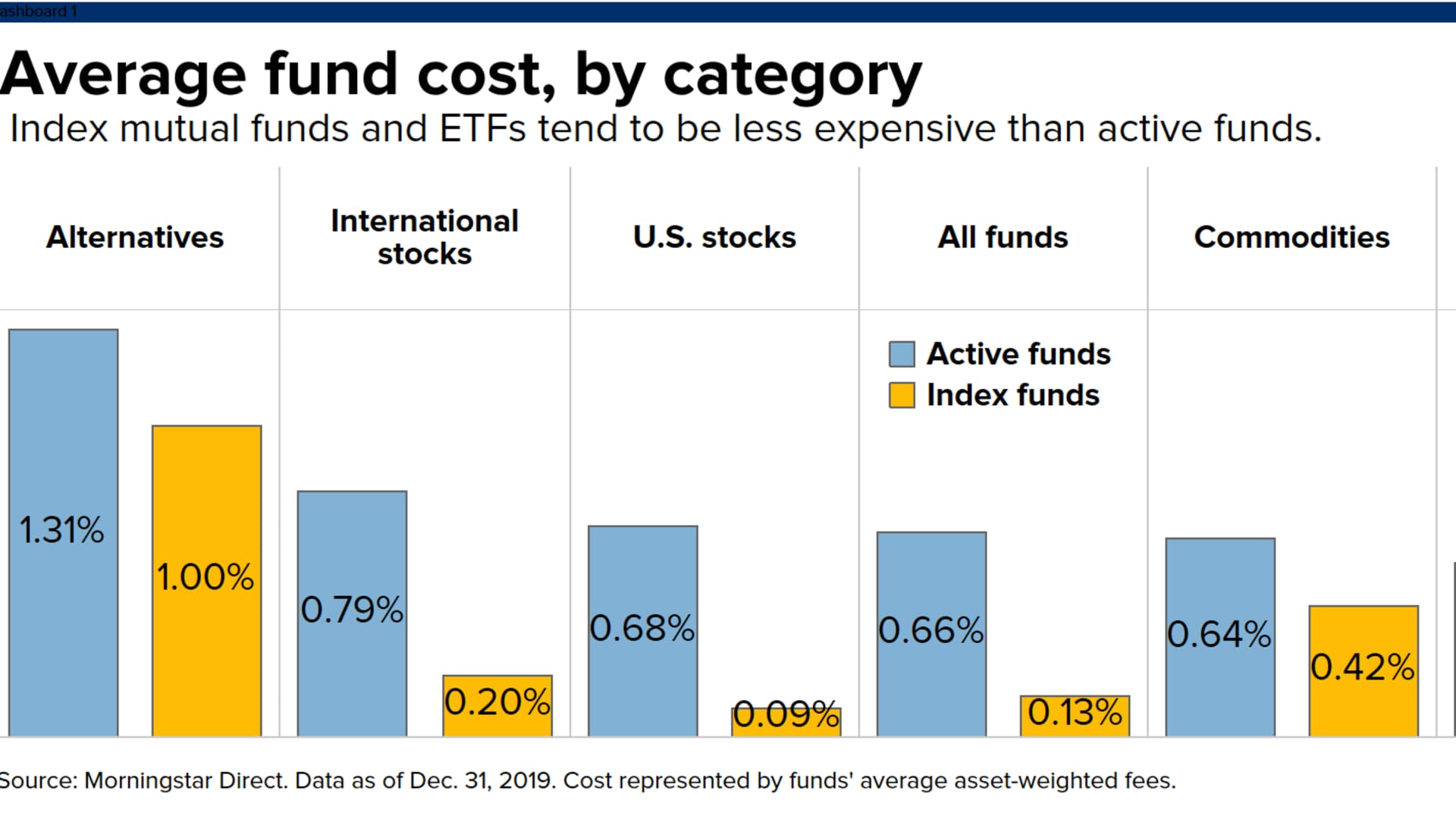

- The average investor pays about five times more to own an active fund relative to an index fund. This makes it tougher for active funds to outperform index funds, after fees.

- However, the lowest-cost active funds tend to beat the average index fund in categories like junk bonds, foreign stock and global real estate.

Some types of mutual funds carry a bigger price tag than others — but that doesn't necessarily mean investors should avoid them.

In fact, there are certain areas where actively managed funds, which carry higher costs, tend to yield a greater net return over the long term than index funds, their lower-cost counterparts.

More from Advisor Insight:

A lot of taxes could be around the corner for these investors

The right way to avoid tax pitfalls of a rollover

Consumers lost $17 billion to identity fraud in 2019. How to prevent it

For example, active "junk" bond and foreign stock funds tend to outperform their passive rivals after fees, according to Morningstar, which tracks investment data.

"There are areas in the marketplace, I believe, that can be better exploited by the active fund manager," said certified financial planner Charlie Fitzgerald, principal and financial advisor at Moisand Fitzgerald Tamayo, based in Orlando, Florida.

Active vs. passive

Money Report

Mutual funds and exchange-traded funds bundle investments, like many different company stocks, to diversify risk. Collectively, U.S. funds held about $28 trillion as of September, according to the Investment Company Institute.

Actively managed funds are more expensive, since fund managers constantly shift around their stock and bond holdings to try boosting returns.

Index funds, also known as passively managed funds, are less costly. They track the stock market instead of trying to beat it. There's no active stock-picking involved.

Index funds cost about five times less than active funds. An investor with $10,000 in the average index fund paid about $1.30 annually to own that fund in 2019, while an active fund holder paid $6.60, according to Morningstar.

Those cost differences, though they appear small, can amount to thousands of dollars over the long term.

Active funds hold the majority of Americans' wealth, but their share has steadily declined as investors seek out lower costs.

Index funds held 41% of U.S. mutual fund and ETF assets as of March 2020, up from 3% in 1995 and 14% in 2005, according to a paper published by the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston.

Drag on returns

Higher cost acts as a sort of drag on investment performance. Managers have to achieve greater returns to beat index funds in order to overcome their larger fees.

Only 24% of all active funds beat the average of their rival index funds in the decade ended June 2020, according to Morningstar.

"If you can start in a relatively shallower hole, odds are you can get out of that hole relatively easier," Ben Johnson, CFA, Morningstar's director of global exchange-traded fund research, said of index funds' lower price point.

However, active funds sometimes beat their index rivals, especially in certain categories.

About 63% of actively managed high-yield bond funds (also known as junk bonds), 60% of global real estate funds and 54% of emerging markets funds beat their index counterparts over the 10-year period through June 30, according to Morningstar.

These were the only investment categories over the decade when odds favored investors relative to index funds.

Though, even here, cost plays a role.

Investors would have only received these better odds if they chose from among the cheapest 20% of active funds. Index funds beat the highest-cost active funds in all categories over that time period.

Investors and financial advisors that chose wisely benefited from higher returns.

The average investor in an active global real estate fund got a 1.2-percentage-point higher net return over the last decade versus its index counterpart, for example, according to Morningstar. Investors also eked out a 1.4-point higher net gain from Europe stock funds, for example.

Ultimately, investors and financial advisors must decide if investment categories like emerging markets and junk bonds make sense in their overall portfolio, said Fitzgerald, whose firm almost exclusively uses index funds with clients.

Such categories may carry more risk for investors, he said.

"It's still not a guarantee you'll pick a manager who doesn't falter," Fitzgerald said.