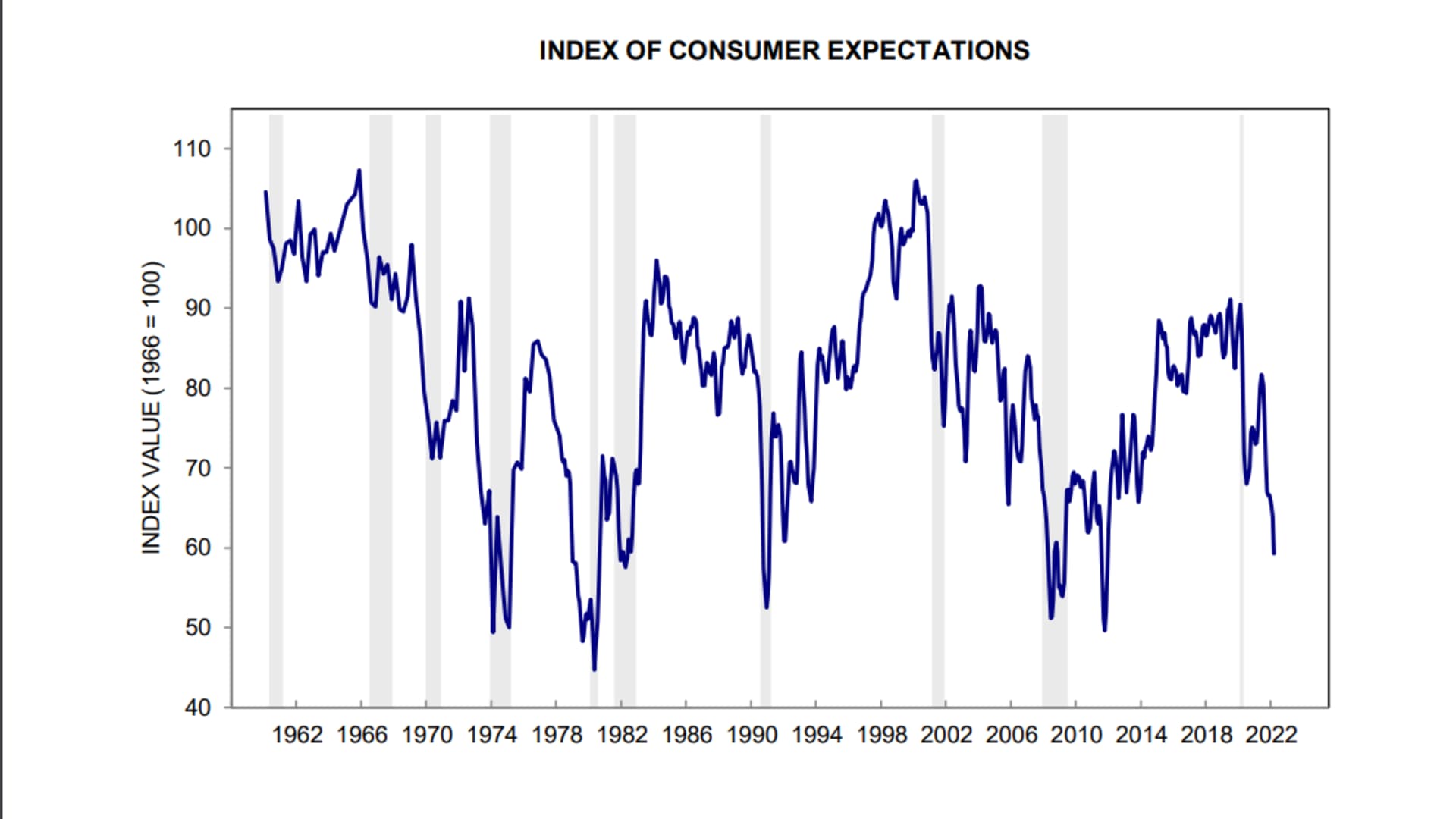

- The latest reading from the University of Michigan's consumer survey finds that the percentage of Americans who expect their personal finances to be worse in a year has reached its highest level since the mid-1940s.

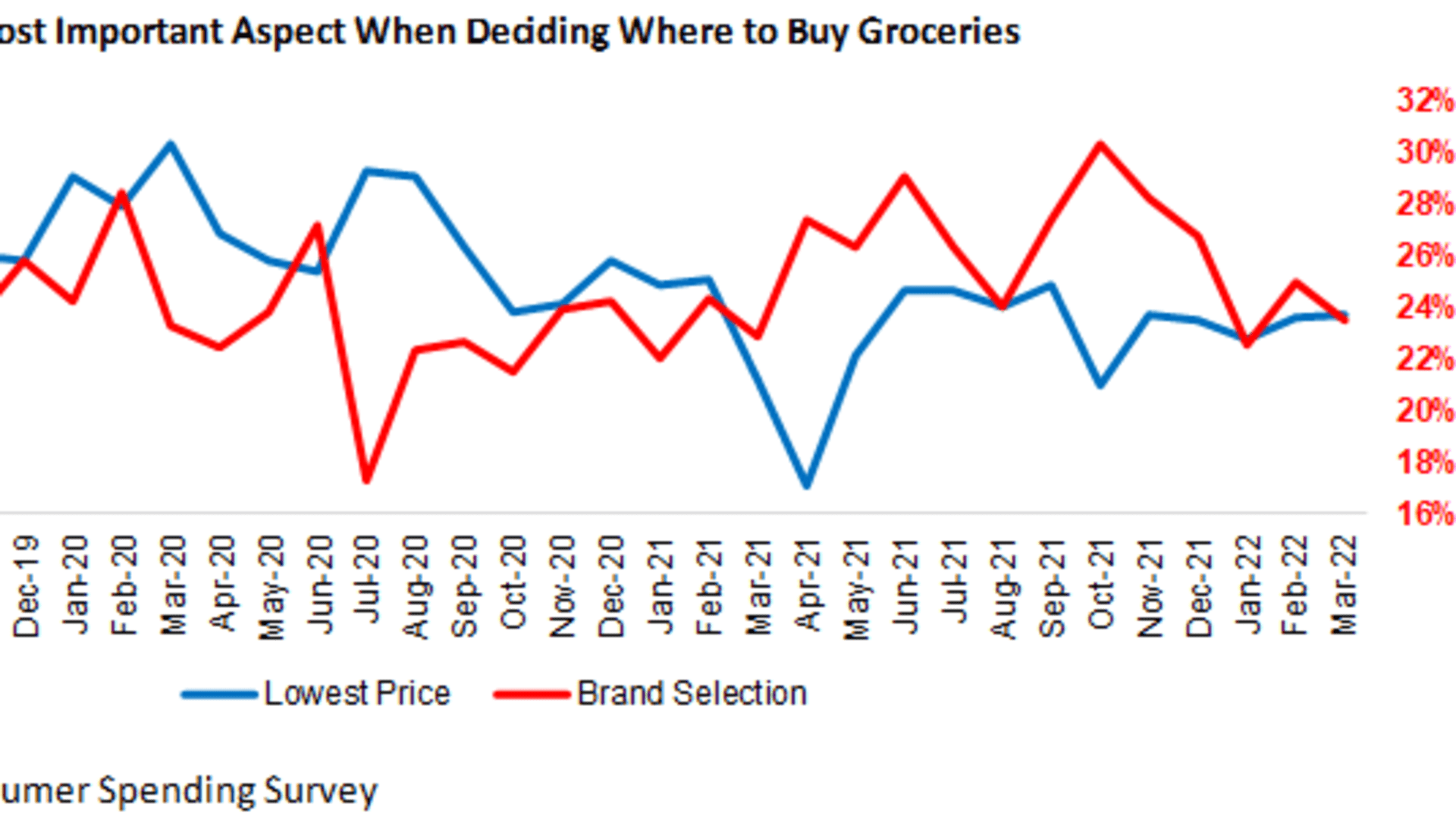

- There are growing concerns, and some signs, that grocery shoppers will "trade down" on the shelf in the months ahead.

- So far, wage increases and job market confidence, high savings rates helped by Covid stimulus, and higher-income consumers who make up the majority of spending, are keeping the economy strong.

A big question on the minds of both Wall Street and C-suites across corporate America is the strength of the consumer, namely, how long can it last?

At some point, consumers will begin to balk at higher prices brought on by demand shocks, supply chain disruptions and surging energy prices. But they have not yet. So far, companies have been able to pass along higher costs, and consumers have been willing to pay. Higher wages, job market confidence, and the historically high rate of savings among Americans that has yet to be fully tapped are all contributing to present economic strength.

The latest data from early earnings reports is encouraging. Last week, General Mills' quarterly results showed no sign of consumers looking to "trade down" on the supermarket shelf.

Get Connecticut local news, weather forecasts and entertainment stories to your inbox. Sign up for NBC Connecticut newsletters.

"If General Mills is any indication, all is good," said Stifel analyst Chris Growe. "I don't want to exaggerate, but their performance this past quarter was strong, in relation to expectations, and their guidance was even better."

Double digit pricing increases in its most recent quarter, along with cost savings, will more than offset inflation for the company, according to Stifel's analysis.

"There is so much pricing coming through (up nearly 11% in the month of February for our large-cap food companies) that it will actually be sufficient to offset inflation," Growe said. "There is an increasing degree of confidence in the relatively near-term around this pricing/cost balance taking hold."

But how long this situation lasts as a good one for both bottom lines and pocketbooks is on Wall Street's mind. Inflation is not backing down, so getting pricing up is just keeping gross profit dollars flat for most companies. And Stifel is finding in its recent survey data more consumer concern about grocery prices. "That could lead to greater levels of elasticity for the branded food products. With private label products on average roughly 35%-40% below the price of branded food we could start to see some trade down activity," Growe said.

It hasn't happened yet, but CFOs of major corporations tell CNBC it is a factor to monitor into the second half of 2022.

Money Report

"It could start to happen in the coming months and higher elasticity could slow that benefit from all of the pricing," Growe said.

Elasticity, a measure of the relationship between movement in price and consumer demand, has broken with history this year. But it's safe to say the consumer is on edge.

Last Friday's University of Michigan Survey of Consumers for March found that expectations among Americans that their personal finances would worsen in the year ahead grew by the largest proportion since the survey started in the mid-1940s. Half of all households anticipate a decline in inflation-adjusted incomes in the year ahead. Inflation was a big part of the story, with more consumers mentioning reduced living standards due to rising inflation than any other time except during the two worst recessions in the past 50 years: from March 1979 to April 1981 and from May to October 2008.

Nevertheless, University of Michigan survey director Ricard Curtin says the consumer remains strong, with confidence in the rising wages and employment opportunities — over 4 million Americans quit their jobs in February — likely to sustain moderate spending growth for the foreseeable future. What's more, the stimulus packages that led to elevated savings continue to bolster the spending power of upper income households, even if lower-income consumers have less firepower.

The Conference Board's latest monthly confidence index reading on Tuesday showed this gap between the present and future, with present confidence slightly higher in March and up for the first time this year, a sign the economy remains strong, but expectations dipping again, with consumers citing rising prices, including gas prices.

Gallup's latest survey of Americans out on Tuesday morning found roughly one in five Americans (17%) saying the high cost of living, or inflation, was the most important problem for the nation.

The importance of the high-income spender to the economy

The high-income consumer is key, notes Mark Zandi, chief economist at Moody's, with the one-third of upper income bracket consumers representing 75% of all spending in the U.S. economy. "If the high income consumers are out buying, we won't see a big impact on raw consumer activity," Zandi said.

For low-income households — by some estimates, over 60% of U.S. households are living paycheck to paycheck — high gas prices haven't hit yet because they came into this cost of living change with excess savings and have been getting strong wage increases on top of that. "They are living paycheck to paycheck, but have not had to pull back on spending yet, but that is coming," Zandi said. Between the higher gas prices and excess savings starting to get paid down, Moody's expects lower-income consumers to start being more cautious this spring.

A third of all consumers in the Michigan survey spontaneously mentioned that inflation has reduced their living standards already, and gas prices and food prices are the two most frequent purchases of consumers. As those prices go up, the pain will increase, Curtin said. But so far, "consumers are saying if 'I don't buy now, it will only cost more later.' So you have anticipatory buying and that is a self-generating cycle," he added. While the Russia-Ukraine war is a wildcard inflation factor for both food and energy, he said the data suggests there is a good chance companies can pass through costs for the rest of year and consumers will be receptive.

Consumer sentiment readings are not a perfect tell, either, given the pandemic era angst, now combined with inflation and a war in Europe. But even if sentiment is swayed by these factors — as well as politics, which Curtin said has been rising as a partisan divide in the data — the recent data show that consumer sentiment is fragile.

"Look to the discretionary items and spending on meat, steak, start to come down, or you start to see less dining out at restaurants that cater to lower- and middle-income households, the chain restaurants," Zandi said. "When they are trading down in various consumer items, that's the real tell."

Zandi is also watching the cracks in the housing market that are already becoming evident in pending home sales and existing home sales rolling over. "We would expect housing price growth will hit the wall pretty soon, and we may even see some weakening in prices, not next month, but certainly by this time next year," Zandi said.

Housing market prices have been strong, and this is key because not only is housing the most rate-sensitive sector of the economy, and already showing signs of stress as mortgage rates rise, but the damage that is inevitable is a key to how the U.S. consumer feels about their overall finances. When people buy and sell homes they make a lot of other purchases too, from cars to furniture to home improvement, and it drives a lot of additional consumer activity. "The ripple effects will be significant, and the other link is house prices and people feeling they have equity, feeling better about borrowing against cards," Zandi said. "It just doesn't feel like that can continue. It feels tenuous."

Michigan's survey of consumer expectations has a long track record of forecasting recessions throughout the post-World War II period. It falls in advance of an economic downturn, on average six months to a year ahead, and it is falling now. "We are in for a difficult time," Curtin said.