- As coronavirus cases and related deaths surge, experts are questioning the ethics of how governments plan to distribute the first vaccines.

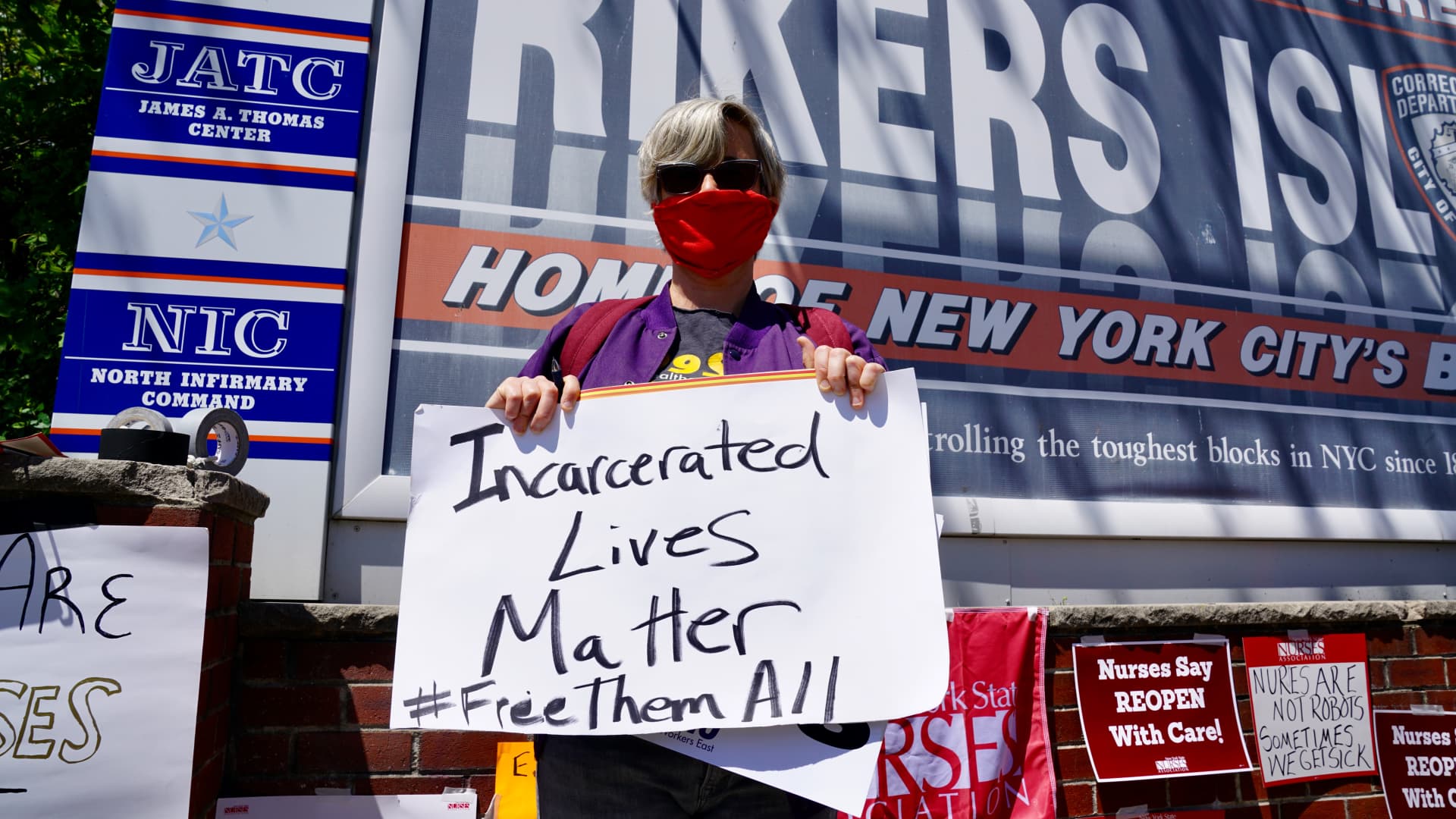

- Incarcerated individuals in the U.S. are almost four times more likely to become infected than people in the general population — and twice as likely to die, according to a study by a criminal justice group.

- "If the biggest hotspots for COVID are prisons, doesn't it make sense to inoculate everyone from the guards to the prisoners?" said Ashish Prashar, a justice reform advocate at Publicis.

With the U.S. and U.K. rolling out national vaccination programs to curb the spread of the coronavirus, health experts and advocates alike are deeply concerned about the notable absence of prison populations in inoculation plans.

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has not yet made any decisions about prisoners when it comes to vaccine access, though it is thought prison staff may be included in the second phase of allocation.

In the U.K., the Joint Committee on Vaccination and Immunisation has said the top priority for the COVID-19 vaccination program should be to prevent death and support the maintenance of health and social care systems.

There is no specific mention of prisons in the committee's guidance, but it is understood the allocation plans will be applied similarly to those incarcerated.

Both countries have administered the first shots of the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine outside of trial conditions in recent days, boosting hopes that a mass rollout of safe and effective vaccines could soon bring an end to the pandemic.

However, as coronavirus cases and related deaths continue to surge, experts are questioning the ethics of how governments plan to distribute the first vaccines.

Money Report

"We are facing a real big dilemma here," said DeAnna Hoskins, president and CEO of JustLeadershipUSA, a national justice reform organization that seeks to cut the U.S. correctional population in half.

Speaking at a Chatham House webinar earlier this month, Hoskins said incarcerated individuals were "still considered less than human … and we are responding in that way as well when we start talking about access to vaccines."

COVID hotspots

Health officials have been warning about the dangers of epidemics for those incarcerated for years, citing an inability for people to maintain safe physical distancing in correctional facilities because of their confinement in small shared spaces.

The pandemic has seen America's jails and prisons become Covid hotspots. Incarcerated individuals are almost four times more likely to become infected than people in the general population — and twice as likely to die, according to a study by the National Commission on COVID-19 and Criminal Justice.

The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices for the CDC has recommended health-care providers and residents and employees of long-term care facilities receive the vaccine in "Phase 1a" of the distribution plans. It has said police and corrections officers, among others, will be included in "Phase 1b."

In addition to the American Medical Association and others, the National Commission on COVID-19 and Criminal Justice has called for prisoners to be inoculated during the initial phases of allocation along with other essential workers in the criminal justice system.

"From my perspective, and the information we have, we need to consider where prisoners fit in terms of their risk in relation to other high-risk groups," Dr. Seena Fazel, a University of Oxford psychiatrist, said in a report published in The Lancet medical journal last week. "On the face of it, prisoners would be high-risk for a few reasons."

Fazel said prisoners were at high risk of contracting the coronavirus because of underlying chronic conditions, age and the environment. He cited a systematic review of prison settings carried out by his team that identified correctional facilities as high-risk settings for the transmission of a contagious disease, with considerable challenges in managing outbreaks.

"Our research suggests that people in prison should be among the first groups to receive any COVID-19 vaccine to protect against infection and to prevent further spread of the disease," he said.

The CDC has recommended that those at increased risk of infection and mortality to the coronavirus should be vaccinated early on, but while federal officials say corrections staff should receive priority access to a vaccine, they have not yet advocated for prisoners to receive the same allocation.

The agency referred CNBC inquiries to the U.S. Bureau of Prisons, which did not immediately respond to a request for comment.

Arthur Caplan, professor of bioethics at New York University Grossman School of Medicine, said in The Lancet report that he does not agree with plans to vaccinate only prison staff.

"If they're at risk and they're older or sicker, they should just get vaccinated. If they're in conditions that don't allow them to isolate, they should get vaccinated. I see no reason to distinguish."

Racial disparities

"If the biggest hotspots for COVID are prisons, doesn't it make sense to inoculate everyone from the guards to the prisoners?" said Ashish Prashar, a justice reform advocate and senior director of global communications at Publicis.

Speaking at the Chatham House webinar on Dec. 4, Prashar said: "All of the guards, all of health care workers, all of the individuals that go in and out of prison are spreading it in society. Wouldn't you start at the hot spots and stop that? And take care of those individuals first?"

Mass incarceration in the U.S. does not impact all communities equally, with African Americans disproportionately imprisoned.

In addition to racial disparity within the U.S. criminal justice system, an updated report by the CDC earlier this month found that, when adjusted for age, Hispanic and Black Americans were found to die as a result of coronavirus at a rate of almost three times that of White Americans.

"Half a million people have not been convicted of a crime, but we have deprived them of their liberty," said Celia Ouellette, founder and chief executive of Responsible Business Initiative for Justice, a not-for-profit group that works to increase safety across systems of criminal justice and incarceration. Her comments referred to those in the U.S. who have not been convicted of a crime but are being held in jails.

"So, there is a moral obligation to treat those people the same as the surrounding community — or potentially better because they don't have the access to the same choices that surrounding communities do."

"We need to stop thinking about inmate populations as a category of people and start thinking of them as people in the same way that we do in the communities around prisons and jails," Ouellette said at the Chatham House webinar.