Jose Collado settled in at a clean white table in a sunlit room, sang a few bars and injected himself with heroin.

After years of shooting up on streets and rooftops, he was in one of the first two facilities in the country where local officials are allowing illegal drug use in order to make it less deadly.

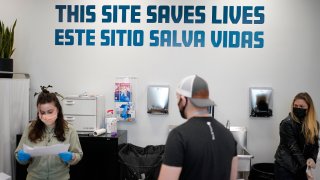

Equipped and staffed to reverse overdoses, New York City’s new, privately run “overdose prevention centers” are a bold and contested response to a storm tide of opioid overdose deaths nationwide.

Supporters say the sites — also known as safe injection sites or supervised consumption spaces — are humane, realistic responses to the deadliest drug crisis in U.S. history. Critics see them as illegal and defeatist answers to the harm that drugs wreak on users and communities.

Get top local stories in Connecticut delivered to you every morning. Sign up for NBC Connecticut's News Headlines newsletter.

To Collado, 53, the room he uses regularly is simply “a blessing.”

“They always worry about you, and they're always taking care of you,” he says.

“They make sure that you don’t die,” adds his friend Steve Baez. At 45, he’s come close a couple of times.

Health

In their first three months, the sites in upper Manhattan’s East Harlem and Washington Heights neighborhoods halted more than 150 overdoses during about 9,500 visits — many of them repeat visits from some 800 people in all. The sites are planning to expand to round-the-clock service later this year.

“It’s a loving environment where people can use safely and stay alive,” says Sam Rivera, the executive director of OnPoint NYC, a nonprofit that runs the centers. “We’re showing up for people who too many people view as disposable.”

Supervised drug-consumption sites go back decades in Europe, Australia and Canada. Several U.S. cities and the state of Rhode Island have approved the concept, but no authorized sites were actually operating until New York's opened in November(researchers have documented an underground site in an undisclosed U.S. location for several years). New York's announcement came six weeks after the U.S. Supreme Court let stand a lower court ruling that a planned Philadelphia site was illegal under a 1986 federal law against running a venue for illicit drug use.

Despite winning the Philadelphia case, the U.S. Justice Department indicated last month it might stop fighting such sites, saying it was evaluating them and discussing “appropriate guardrails.”

New York City's only Republican in Congress, Rep. Nicole Malliotakis, has pressed the Justice Department to shutter what she sees as “heroin shooting galleries that only encourage drug use and deteriorate our quality of life.”

She has proposed to strip federal money from any private group, state or local government that “operates or controls” a safe injection site. (Her efforts spurred a protest in lower Manhattan Wednesday by VOCAL-NY, a social service group interested in eventually opening a consumption site.)

Another New Yorker in Congress, Democratic Rep. Carolyn Maloney, is a leading sponsor of an addiction-fighting proposal that could make money available for such facilities. Organizers say the New York sites currently run on private donations, though their parent group gets city and state money for syringe exchange, counseling and many other services offered alongside the consumption rooms.

Several state and city officials have embraced them. But they also fueled a December protest that drew over 100 people, including U.S. Rep. Adriano Espaillat, a New York Democrat, to complain that drug programs, in general, are unfairly concentrated in the injection sites' neighborhoods and kept out of whiter, wealthier areas.

“The safe consumption site is doing God’s work, but they’re doing it in the wrong place,” says Shawn Hill, who co-founded a neighborhood group called the Greater Harlem Coalition.

People bring their own drugs — of whatever type — to the consumption rooms, but they're stocked with syringes, alcohol wipes, straws for snorting, other paraphernalia and, crucially, oxygen and the opioid-overdose-reversing drug naloxone.

Staffers, some of whom have used illegal drugs themselves, watch for signals of overconsumption or other needs, from advice on injection technique to more complicated help.

Resting a supportive hand on the shoulder of a slumping, dejected man, Adrian Feliciano encouraged him to talk with a mental health counselor — and brought one in — on a recent afternoon.

“For a lot of our folks, just providing a safe space is an introduction to services,” Feliciano, the center's clinical and holistic care director, said afterward.

For all the services it offers and the overdoses it has turned around, OnPoint has also come up against its limits. During a 10-day span in February, two regulars died and a third was in a coma for a time after apparent overdoses elsewhere when the sites were closed at night, according to senior program director Kailin See, who believes longer hours would have saved those who died (the third person recovered).

There have been no recorded deaths in supervised injection facilities in countries that permit them, and there’s some evidence linking them to fewer overdose deaths and ambulance calls in their neighborhoods, according to a 2021 report that compiled existing studies.

The report, by the Boston-based Institute for Clinical and Economic Review, found no link between safe injection sites and the rates of various crimes, though public drug use dropped off in some places.

“If you believe in harm reduction, here's harm reduction that saves you money” in ambulance runs, said Dr. David Rind, the think tank's chief medical officer.

But to Jim Crotty, a former Drug Enforcement Administration official during the Obama and Trump administrations, the sites' lifesaving purpose comes at steep social cost.

“The goal can’t simply be to keep people alive,” said Crotty, who argues that policymakers should concentrate instead on expanding drug treatment. “If you believe, like me, that doing drugs is very destructive, then the goal has to be to stop doing drugs.”

Rivera, for his part, stresses the need to stanch the flow of drugs into the U.S., rather than what he sees as blaming people in poor communities “for using the drugs that were let in.” OnPoint says staffers regularly foster, but don’t force, conversations about treatment, which many clients have already tried.

“You need to be alive to try again,” See says.

Collado has tried to quit drugs, stopping at times during his four decades of using, he said. Like many of people who use the consumption rooms, he lives on the streets.

He and Baez look out for each other. They've helped one another solve problems, shared money when one was broke, and tried to make sure that neither would overdose and die alone. The room, and everything offered along with it, fill that last role now, and more.

“This is my home right here,” Collado said. “This is my family.”