As the USS George Washington reeled from a spate of suicides two years ago, Navy leaders reacted with anger and denial while discussing news coverage of the deaths and whether to promote the sailors posthumously, according to emails obtained by NBC News.

After five sailors assigned to the aircraft carrier died by suicide within a year, including three in one week in April 2022, some of the ship’s commanders dismissed claims about poor living and working conditions, and at least one of them admitted to having a weak grasp of the mental health issues that plagued his sailors, the messages show.

“I myself, have an extremely limited understanding of mental health issues and have a very hard time understanding why,” William Mathis, the executive officer, wrote in one of the roughly 130 emails the Navy recently provided, nearly two years after NBC News filed a Freedom of Information Act request.

Get top local stories in Connecticut delivered to you every morning. Sign up for NBC Connecticut's News Headlines newsletter.

At the time, several sailors said their struggles were directly related to a culture in which seeking help was not met with the necessary resources, as well as the unbearable state of the ship while it was docked and undergoing a lengthy overhaul in Virginia.

The deaths sparked investigations, prompted visits from the Navy’s most powerful officials and led to the relocation of more than 280 sailors.

U.S. & World

For at least one sailor’s family, the years have done little to heal wounds.

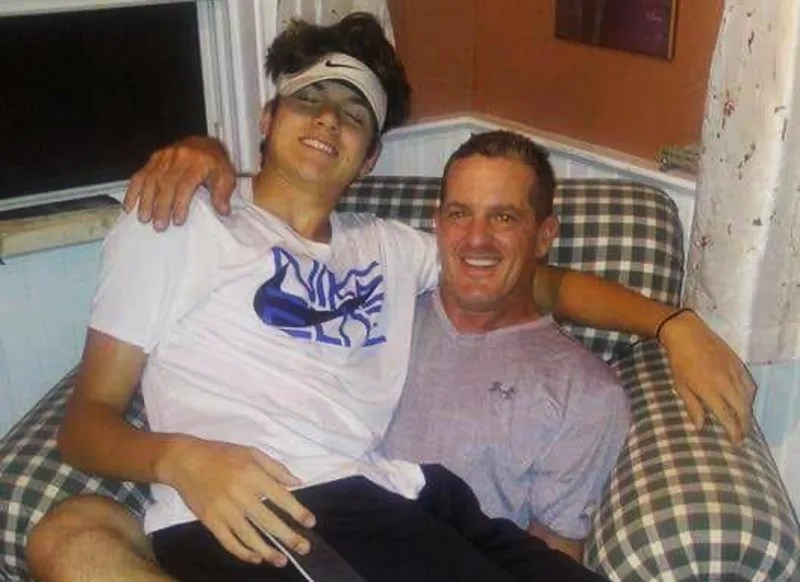

“It’s still fresh, and it seems like they swept it under the carpet and moved on,” said John Sandor, whose 19-year-old son, Xavier, had long complained about the George Washington before taking his own life on the ship.

A string of tragedies

Mika’il Sharp, 23, died by suicide on April 9, 2022, at a family gender-reveal party in Portsmouth, Virginia. He had gotten married in the last year and had been promoted days prior, according to his family and the findings of a Navy investigation.

After Natasha Huffman, 24, ended her life the next day, the Navy began discussing whether the two should be promoted posthumously.

They appeared eligible for such advancements, a Navy program manager wrote to the ship’s leaders on April 12, 2022. Under the Navy’s guidelines, any sailor who dies in the line of duty and meets certain eligibility requirements can be posthumously advanced.

Brent Gaut, the ship’s commanding officer, appeared supportive of the promotions and said he would deliver a decision shortly.

On the morning of April 15, 2022, Mathis, who began his role as Gaut’s second-in-command two months earlier, emailed behavioral health care doctors on his team to see if the Navy could have done anything to prevent Sharp and Huffman’s deaths.

“I am not trying to point fingers at anyone else,” Mathis wrote. “Hoping to learn something to take forward.”

Gaut, Mathis and Christopher Zeigler, the third-in-command, were “starting to see more and more gripes about lack of access to mental healthcare,” Mathis wrote to the physicians, as he set up a meeting to discuss the issue.

“It seems to me that we probably have a lack of supply to meet the demand,” he said. “I need a better understanding here as well.”

That night, while working his usual 12-hour shift on the ship, Xavier Sandor stepped inside a bathroom and told his parents in a text message that being home was the only thing that made him happy, according to his father. He asked to be buried near his high school friend before taking his life.

His mother read the message first and let out a painful howl. His father raced down the hall of their Shelton, Connecticut, home, which Xavier had walked through that morning.

By the time the Sandors arrived at the Riverside Regional Medical Center in Virginia, where Xavier was taken, he was gone. John Sandor, 51, fell to the floor in anguish.

“The doctor got on his knees with me and said he did everything he could,” he said.

In Tennessee, where he was on leave, Gaut, who is now 53, had a “mini panic attack,” he said in an email. His deputy sent out a mass email to department heads, alerting them to the third death of a freshman sailor in six days.

“I know most of you are already aware, but I regret to inform you all that we had another apparent suicide last night,” Mathis wrote.

“Call all of our folks and give them a verbal hug,” he continued. “Let our Sailors know that we had another tragic event last night and remind them that they are loved and that there are resources available if people are struggling.”

Two days later, Mathis, now 46, questioned the posthumous promotions.

“I am now in the anger phase of grief so I realize that is affecting my judgement,” he wrote. “But I am not seeing how a Sailor committing suicide should warrant a posthumous advancement.”

Gaut, Mathis and Zeigler directed comments to the Navy. A Navy official said the emails are a "snapshot and do not fully represent the level of care and support" the commanders took to immediately help their crew.

The official said the correspondence "reflects a period of time in which Navy leadership were working to provide council, guidance and comfort to the crew."

Of the three sailors who died that week in April, Huffman was posthumously promoted, the Navy said. Sharp was not eligible because he had recently advanced, and Sandor had not taken the advancement test that would have made him eligible, according to the Navy.

Facing the public, missed red flags

The next week, as the deaths made national headlines, the ship’s leaders began to brainstorm how to share the news.

Gaut asked a public affairs officer to start thinking about a Facebook post that would tell families “what happened and the way forward,” but the idea was quickly shut down.

“There is nothing we can say other than what has been said,” the press officer wrote. “A social post will only attract negative attention.”

The public affairs team sent Gaut a draft of “talking points” to consider when addressing the sailors. Mathis reviewed the memo, which confirmed five deaths by suicide since December 2021.

“I thought briefly that maybe we should discuss data up to 12 months ago but I changed my mind and thought we should just focus on the 9‐10 months you have been in command,” he wrote to Gaut.

A Navy investigation released publicly in December 2022 determined that Sharp and Huffman’s deaths were not related to life onboard the ship, but Xavier Sandor’s was. A separate investigation found that the shipyard lacked sufficient parking, transportation and access to food and housing.

Ten days after Xavier’s death, Gaut remained adamant that the suicides were not related to the ship’s conditions. He wrote to a colleague that he was staying off social media because he knew “this was not a quality of life issue.”

A month after the deaths, Zeigler still dismissed claims about problems on the ship when a local pizzeria owner wrote the leaders with an offer to send 420 free pies, one to each of the sailors believed to be living onboard.

“The issues we have aren’t because of the exaggerated media stories of our living conditions so just want to make that perfectly clear before we move forward,” Zeigler, now 50, wrote.

From 2017 to 2023, the George Washington was docked at the Newport News Shipyard in Virginia, where it underwent significant repairs and upgrades.

While most of the roughly 2,700 sailors went home after their shifts, hundreds who lived out of state or didn’t have off-site housing stayed on the vessel, where several sailors said there was constant construction noise and a lack of hot water and electricity.

For three months, Xavier, who was over 6-feet tall, lived in his Toyota Corolla and made 16-hour round trips back home when he could to escape the George Washington, his father said. Those drives usually happened every other weekend.

“He’d crash for most of the two days and then drive back,” John Sandor said.

Shortly before his death, Xavier skipped a meeting with Zeigler to go home. It was a punishable offense, but the ship’s leaders failed to properly document the infraction, which would have given them a reason to temporarily take away his firearm and potentially see that he was struggling to adapt to shipyard life, investigators said.

In the three days before he died, Xavier got a maximum of about 14 hours of total sleep, which likely affected his decision-making ability, according to the investigation.

His father said he will blame himself forever for not seeing the red flags, but he blames his son’s commanders for missing them, too.

“He shouldn’t have been armed,” John Sandor said. “My son should have never been put in that situation.”

Nine sailors died by suicide during the roughly six years the George Washington was docked in Virginia, Navy spokesperson Sandra Gall said.

After the spate of deaths in April, the Navy gave the sailors more mental health resources, including psychologists, social workers and chaplains. Before, there had been only one psychologist on the ship.

Leaders also amplified communication efforts, hosted morale-boosting events and provided shuttles to ease parking woes, Gall said.

"Navy leadership remains fully engaged with the crew to ensure their health and well-being, and to ensure a climate of trust that encourages Sailors to ask for help and provide quality of service feedback," Gall said.

Today, the Sandors sit and mention Xavier’s name as much as they can. They no longer host holidays in their home, which they’ve filled with photos of the young sailor and where they display the folded American flag they were given at his funeral.

Xavier’s goldendoodle puppy, Grace, still waits on his bed every day, anticipating his return, John Sandor said.

“It totally changed our lives,” he said, “and it’s miserable without him.”

If you or someone you know is in crisis, call 988 to reach the Suicide and Crisis Lifeline. You can also call the network, previously known as the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline, at 800-273-8255, text HOME to 741741 or visit SpeakingOfSuicide.com/resources for additional resources.

This story first appeared on NBCNews.com. More from NBC News: